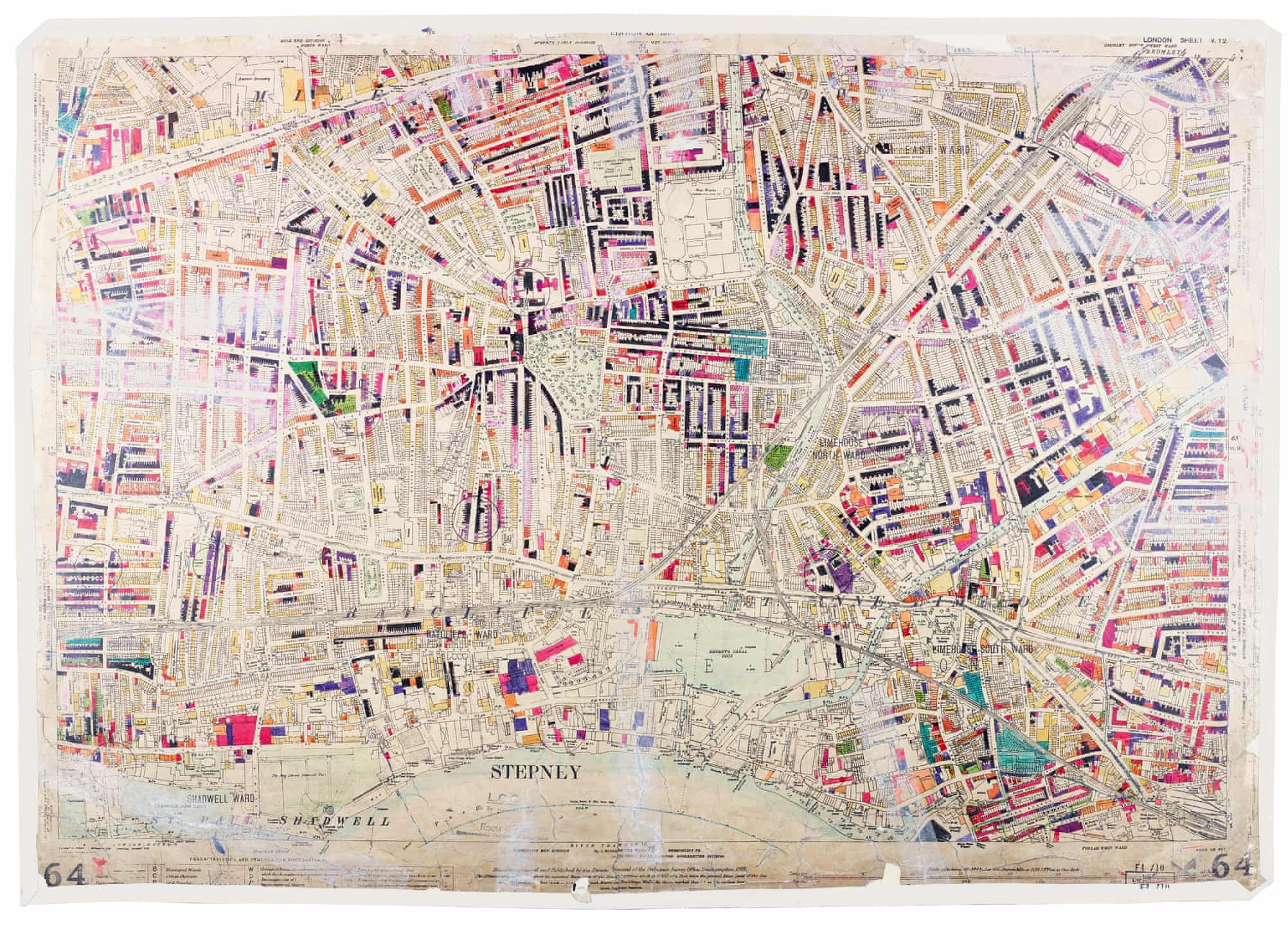

More than 20,000 bombs fell on London in the second world war, destroying or damaging beyond repair 116,000 buildings.

The vast majority of these were recorded and mapped, creating a series of Bomb Damage Maps for London County Council showing colour-coded bomb damage across the city (see below), Originally created to help landowners deal with insurance and compensation claims, the maps were later used for post-war planning; with parks, new estates and office developments filling the bombed-out areas.

Several of today’s pocket parks owe their existence to the bombs that fell and existing parks were changed forever by bomb craters, military installations, shelters, allotments for food or mounds of debris from nearby bombsites.

One of the 'lakes' in Redbridge’s Goodmayes Park, the one adjacent to the Mayfield Estate, was created in February 1945 when a V2 rocket exploded, creating a huge crater. The Barbican and its greenspaces were built over a scene of utter devastation: on 29 December 1940, the entire ward of Cripplegate was razed in firestorms.

Lillie Road recreation ground contains one of the few wartime installations to have survived for 75 years; a redbrick building in the centre, constructed as the firing base for an anti-aircraft gun. A similar building once existed in Bishop’s Park, while the former cricket pavilion in South Park probably played the same role, with a gun sited on the thick reinforced concrete roof.

On the very first day of Britain’s entry into the war, 3rd September 1939, members of the public had to retreat to air raid shelters in St. James’s Park when the inaugural warning sirens sounded. It proved to be a false alarm. Hyde and Greenwich Parks also provided sanctuary, the latter offering three shelters that could house up to 500 people. Parsons Green, Eel Brook Common and Shepherds Bush Green all had large civilian shelters.

Wormwood Scrubs served as a shooting range for troops during the war, but like many parks it also housed anti-aircraft guns. Another anti-aircraft battery was based in Victoria Park. On the 3 March 1943, the sound of its guns was responsible for the accidental death of 173 people at Bethnal Green Tube Station. People mistook the sound for a bombing raid and fled down the stairs into the shelter. Some falling at the foot of the stairs. In fear for their lives, crowds continued to push into the shelter and the deaths were caused in the crush. Like many things during the war, details were kept quiet so they wouldn’t harm public morale.

To boost morale, there was an appeal to donate iron railings and gates for the war effort (pictured below), leaving many homes and parks with metal stumps atop low stone walls, where the railings had been cut down. In some cases, this opened-up what had previously been private and enclosed squares to the public. Goodmayes Park is one of the few parks to retain its gothic-style gates and stretches of railings. Little of the material gathered was suitable for melting down to make tanks, weapons, or planes. There are records indicating much of it was quietly dumped in the Thames Estuary and Irish Sea.

Barrage balloons were often anchored in parks and public spaces. The balloons and their trailing cables deterred low-flying bombers and dive-bombers, forcing enemy aircraft to fly at heights where they were more vulnerable to anti-aircraft guns. By 1944 there were nearly 3,000 barrage balloons protecting London and parts of the UK. The balloons were huge (on average, about 18.9 meters long and 7.6 meters in diameter) that’s about three times the size of a cricket pitch.

With the advent of the V1 flying bombs, the barrage balloons were moved to create a protective fence around the southern perimeter of London, where they proved to be mildly effective against them, officially preventing 213 of the 10,000 V1’s launched at the capital.

Enemy bombers navigated using landmarks visible from the skies to find London, such as the Thames Estuary or from glinting railway tracks and canals. So called “starfish” sites were created around London, in Richmond Park, Farleigh (Now a golf club), Lambourne End (An Outdoor Education Centre), Lullingstone (Also a golf club) and Rainham Marshes in east London. These were decoy sites to protect central London from bombing. The idea was to light a series of controlled fires during an air raid to replicate an urban area targeted by bombs. German bombers would then be tricked into dropping their deadly payload without loss of life or serious damage on the ground.

Rainham Marshes is now part of the RSPB nature reserve at Purfleet, but there are remnants of its military past, such as shooting butts, the walls of the ammunition stores and even an anti-submarine tower, which would have anchored one end of a submerged chain, spanning the Thames, to stop U-boats sneaking up the river.

Upstream from Rainham, 16 marooned concrete barges (Pictured below) lie on the foreshore of the Thames, deliberately scuppered here to reinforce a section of damaged flood defences. There are no official records on the barges, but they are believed to have played a key role in the Normandy D-Day invasion in June 1944. They were primarily used to transport fuel to other ships engaged in the invasion and once emptied, may have formed parts of the Mulberry harbours and pontoon bridges that helped move men and equipment to the shore.

The east end and docklands were repeatedly targeted and have now mostly been redeveloped. Many of the old wharves along the riverfront upstream in Hammersmith and Fulham received direct bomb damage and, post-war, some of these bombsites were turned into parks, such as Bishops Park and the nearby Rowberry Mead playing field. Ealing’s Acton Park got an extension; created on a bomb crater formed after a flying bomb destroyed Nos. 4, 6, 8 and 10 Churchfields Road.

Not all of our post 1945 landscape is the result of the destruction. Some of it was construction, such as the wide green shoulders of railway embankments which create green corridors linking central London with the suburbs and countryside. Anti-tank installations were laid alongside rail lines to contain and delay advancing panzer tanks in the event of an invasion. The rail lines were seen as a vulnerability, allowing quick and easy access to central locations. These large, heavy and reinforced concrete “lozenges” alongside Elmhurst Gardens in Woodford (pictured below) effectively trapped the tanks on the tracks, making them easy targets.

Many parks were used to bury the debris and rubble from bombed buildings. The Regent’s Park, for example, was forever changed after more than 300 bombs rained down on it, including incendiaries and V2 rockets. Areas which once undulated in the 18th century fashion now lie flat because the park was used to bury bomb rubble. Artefacts are still being found; in 2018 a large unexploded bomb was discovered in Hyde Park’s Serpentine lake, and an archaeological dig at Greenwich Park uncovered not only a lost air raid shelter but a tiny lead soldier that had been left inside.

Bushy Park became home to almost 8,000 US troops during the Second World War. In 1942 Camp Griffiss was established in the north-east corner of the park; its central Chestnut Avenue provided an ideal landing strip for aircraft.

The National Physical Laboratory, whose work led to the development of the Spitfire plane, was also based at Bushy and made important advances in aerodynamics and marine technology throughout the war. The Navy conducted tests of Torpoedo designs in the Queen Mother Reservoir near Wraysbury.

Bushy played a crucial part in bringing the war to an end. In February 1944 General Eisenhower moved the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) to the park, taking over some of Camp Griffiss. This is where the initial planning of Operation Overlord took place; the invasion of the European mainland that launched on D-Day, 6th June 1944.

St Paul’s Gardens in Hammersmith and Fulham (formerly St Paul’s Boys’ School) was also commandeered by the army and used as a training ground for British D-Day forces, and to plan the operation.

Private gardens, public squares and pretty much all parks were used for food production. The Dig for Victory campaign got lots of people actively growing. The famous poster image (above) of a boot pushing a spade into the ground was photographed in a west London allotment. The foot belongs to William McKie, a keen member of the Acton Gardening Association.

Ten parks with war memorials:

- USAAF Memorial in Bushy Park.

- Norwegian War Memorial in Hyde Park, also home to a Holocaust Memorial.

- The RAF Bomber Command Memorial was installed in Green Park in 2012, commemorating more than 52,000 aircrew from Commonwealth and European Allied nations who died in the war. The park also contains the Canada Memorial.

- Eagles Squadron Memorial for American fighters in Grosvenor Square Gardens.

- Gwendwr Gardens open space, has a memorial remembering the lives lost in the air raids of 20 February 1944 in what was known as the Baby Blitz.

- Deptford Memorial Gardens is made up of three strips of formal gardens with a Portland stone obelisk and statues of a soldier and a sailor, commemorating those who died in both world wars.

- On the Albert Embankment in Lambeth, there is a monument to the Special Operations Executive, with a bust of Violette Szabo, a former Lambeth resident, who joined the SOE and became a French resistance heroine. She was captured and executed and was the first woman to be awarded the George Cross posthumously.

- Ealing’s Walpole Park and Gardens has a pair of curved walls either side of its Ealing Green entrance with the names of some of those who fought and died in the two world wars.

- Bethnal Green Gardens has a memorial to those who died in what was the worst civilian disaster of WWII, when 173 people were crushed on the staircase trying to enter the bomb shelter in Bethnal Green Tube Station.

- Tavistock Square, famous for its statue of Mahatma Ghandi, also has a tree planted in 1967 commemorating the victims of Hiroshima; and a memorial for conscientious objectors.